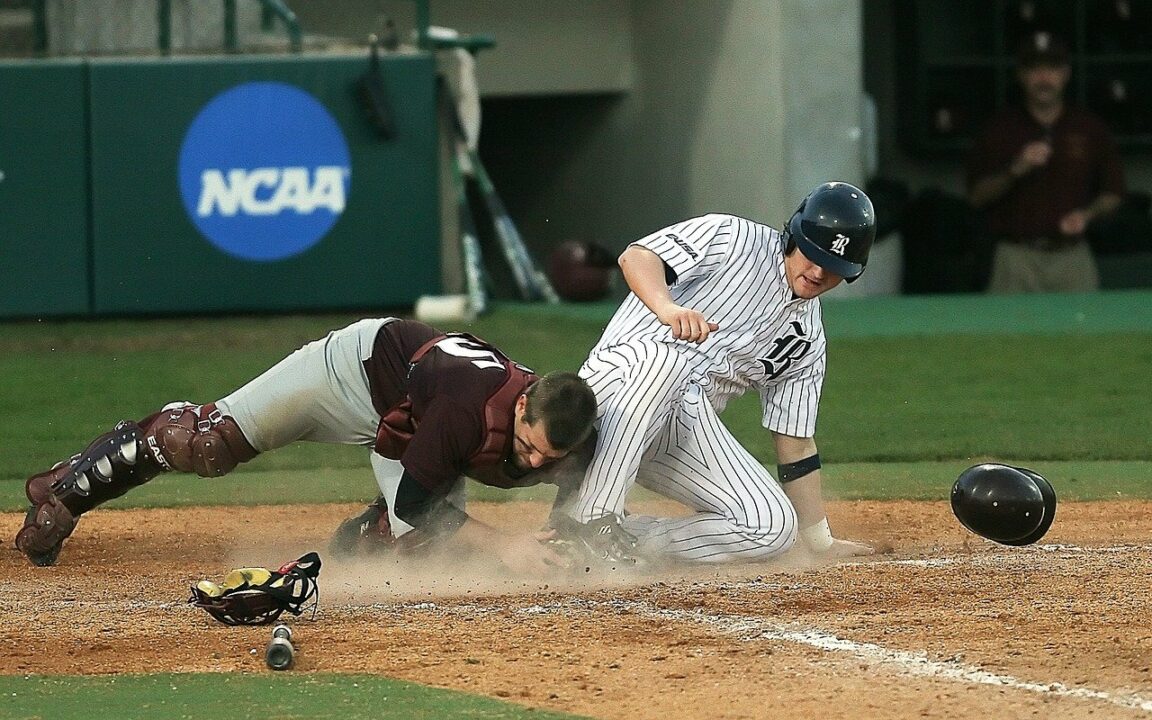

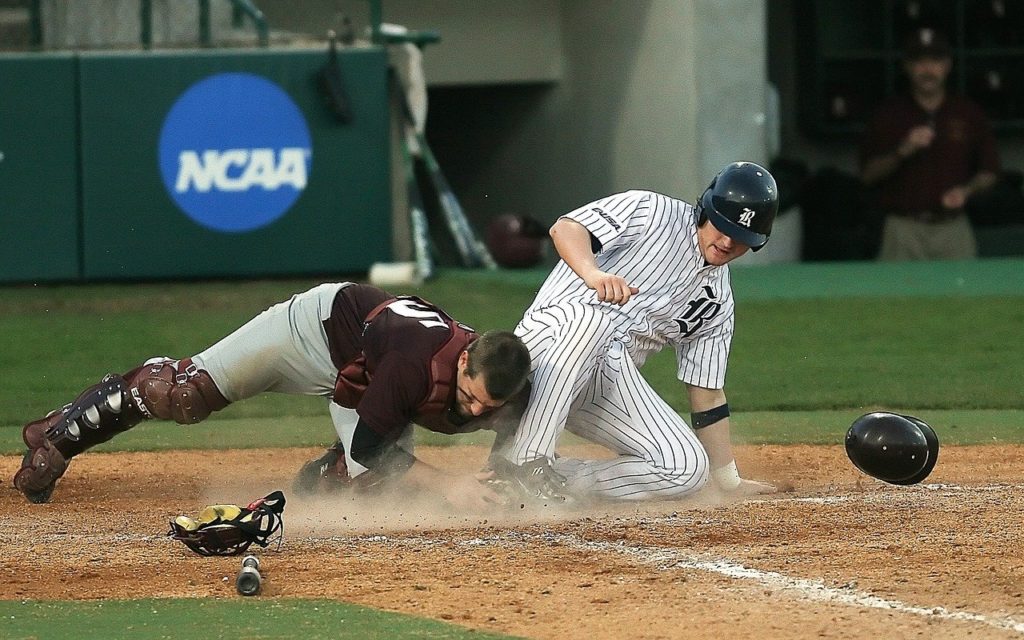

NCAA Athletes: To Pay or Not to Pay?

The United States is the only country in the world that hosts mega-sporting events with amateur athletes (i.e. unpaid athletes) at institutions of higher learning.

The result? A titanic business for the governing body, the NCAA, as well as its’ schools and conferences. Due to the ever-growing popularity of NCAA sports, media and corporations have also gotten involved. Just how influential is the business? In 2019, Zion Williamson, an 18 year old phenom basketball player from Duke University, ripped his shoe in the first 34 seconds of a game. This was not just any game. 4.3 million people were turning in on TV. The U.S. President sat courtside. The result of the ripped shoe? A 1.1% drop in next-day trading for Nike, the maker of the shoe. This loss translates to an estimated $1.1 billion loss in one day for Nike. True, the influence of Zion Williamson is not that of a typical NCAA athlete. Nevertheless, given the enormity of the NCAA and its growth over the last several years, it has come time to look at the complex structure and ask the question – is it time for the NCAA to pay its athletes?

On the business side, the NCAA is an entity that offers student-athletes the opportunity to pursue their education while at the same time competing as amateurs at the highest level. It generates more than $1 billion a year in revenue, which is derived from two main sources – the NCAA March Madness basketball tournament and the 90 NCAA men’s and women’s championships held annually. As they are a not-for-profit, approximately $1 billion is distributed into funds to financially source the NCAA championships, as well as various educational and academic programs. The conferences also make significant revenue, as they own the media rights to all regular season games for all sports, as well as the conference tournaments and the American football Bowl games. The 5 largest conferences, often referred to as the “Power 5”, are projected to make $1.3 billion in 2021 from American football TV/Media rights alone. Additionally, TV/Media viewership numbers continue to climb, with 16.9 and 18.7 million viewers for the men’s basketball and American football Championship Games, respectively. With numbers like those, corporations are fighting for sponsorship and advertising opportunities. The overall value of the NCAA for all stakeholders is currently estimated at over $14 billion in annual revenue.

Opponents of the proposal to pay NCAA athletes argue that if college athletes are on scholarship, they are in essence paid. The average cost of a U.S. college education can average from $22,200 / year for an in-state public school up to $50,800 for a private institution, with some having higher fees than that. For most students, loans are required to pay for a 4 year college education, so athletic scholarships can be a huge financial relief for athletes and their families. However, the chances of getting an athletic scholarship are miniscule, with less than 2% of all U.S. high school athletes getting a scholarship, many of which are partial. The typical day of an NCAA student-athlete is also extremely demanding, and often draws comparisons to professional athletes. In addition to classes and studying, NCAA athletes have commitments to a variety of daily sessions, including but not limited to, practice, strength and conditioning, nutrition, psychology, injury treatment / prevention, media, compliance, and community service. – See here for an example of “A Day in the Life” of a college athlete:

In 2020, the NCAA proposed new legislation which would allow its athletes to make money off their “name, image and likeness”. Examples of this include promoting a business, endorsing merchandise, or representing themselves in a video game. But is this enough? Do athletes deserve more? Or are they already paid in the form of scholarships? In the summer of 2021, the U.S. Supreme Court is set to rule on whether the NCAA has violated antitrust laws by restricting what NCAA athletes can be paid. The NCAA argues that they should be able to determine the line between professional and amateur. What do you think?

About the author

A member of the MAS Class of 2021, Christy is a 2001 graduate of Belmont University where she was an NCAA Division I softball athlete, majoring in Kinesiology. Dukehart then went on to obtain her MBA and Master of Science in Accounting from Northeastern University in 2003, after which she started working for Ernst & Young. After spending 10 years working in international finance, Dukehart opened her own softball academy to train elite athletes and guide them through the NCAA recruiting process. At the same time, she took a softball coaching position at Trinity College, a DIII program. Christy loves to travel and hopes to work abroad after graduation.

–

Latest articles

- AISTS MAS ranked as the World’s No.1 Master in Sports Management

- How to make Sport and Sustainability Compatible

- AISTS x Global Sports webinar – Navigating Sustainability: Insights from Sports Events Experts

- Everything you need to know to develop your sports business

- Introduction: How to Work in the Sports Industry